Messaging, Messengers and Public Support

Overview: The Movement’s Message Problem

By 2009 the marriage movement had lost every one of 30 statewide ballot campaigns designed to ban same-sex couples from marrying. (A victory in Arizona—where the proposal would have also affected opposite-sex couples-- was reversed a year later when the measure passed to restrict marriage to one-man one-woman.) In 2004 alone (the year Massachusetts first began issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples), Republican operatives used anti-marriage measures to galvanize support among social conservatives, driving efforts to put measures on the ballot in 13 states. Those measures were primarily in states where the marriage conversation had barely begun, and they passed by an average margin of 70 percent to 30 percent. Subsequent losses in California (2008) and Maine (2009) – states we’d hoped to win – were particularly devastating. Opponents of the freedom to marry taunted advocates saying that we could never win a vote of the people. We knew that before marriage went on the ballot again, we had some serious challenges to address – our messaging, chief among them.

The marriage movement’s messaging challenges were clear. While we hit majority support nationwide by 2010, there were still many conflicted people who's support was shaky at best. We were not making the case to “conflicted” voters in a persuasive way, and they were crucial to winning at the ballot box. Moreover, we were highly vulnerable to opposition attacks that raised fears that marriage for gay couples would be dangerous to children.

At that point our movement had relied almost extensively on an informational approach that highlighted the 1,138 “rights and benefits” denied to gay couples, appealing to a sense of fairness and justice. An ad from Oregon’s campaign in 2004 became emblematic of this early message approach. In it, a retired state Supreme Court justice wearing a suit, seated in a law library alongside an American flag, intones “The Oregon Constitution is supposed to protect everyone, but that will change if Constitutional Amendment 36 passes. Whenever we meddle with the Constitution, there are unforeseen consequences. Constitutional Amendment 36 could deny gay and lesbian couples the right to visit one another in the hospital or the right to keep their family home after one of them dies. That’s not fair. Don’t use the Constitution to hurt people. Vote no.” See the video below. (To be fair, the Amendment 36 campaign also featured two stories of lesbian couples affected by the Amendment—but we were to learn much later why those two stories did not especially resonate with voters.)

By contrast, our opposition’s ads featured warm footage of a heterosexual couple with their toddler; another ad showed a grandmother pulling her wedding dress out of a trunk in the attic, to share with her granddaughter. This emotionally effective approach won in Oregon and was also employed in the fight over California’s Prop 8 in in 2008. In addition, the opposition’s infamous “Princess” ad raised parental fears that their kids would be taught about “being gay” in schools - and the movement’s tracking polls documented the devastating impact of this scare tactic.

Early Steps to Develop More Effective Messaging: Let California Ring

In the lead-up to the Prop 8 campaign a group of movement leaders already had a sense that our side’s emphasis on rights, benefits, and the intellectual concept of fairness was insufficient. They were also aware that we needed a longer period of time to engage with the general public, outside the late stages of a ballot measure campaign. A public education project called Let California Ring relied on new research, which pointed towards the idea of bringing more emotion into the campaign conversation, appealing to voters’ hearts as well as their heads. Let California Ring, staffed by Thalia Zepatos and led by an Executive Committee composed of Evan Wolfson and other national movement leaders, funders, and leaders of Equality California (EQCA) and community-of-color organizations from across California, created a series of ads featuring real people sharing their values and speaking to their aspirations for the gay and lesbian couples in their lives.

In early 2008, Let California Ring conducted a measured field experiment, taking their program to scale in the Santa Barbara media market, with the Monterey media market (where no similar effort took place) as a control. Santa Barbara efforts included the “Garden Wedding” television ad which made an emotionally compelling case to non-gay people it would be like if they could not marry. This was supported by an online component, earned media, faith and college campus events, and other grassroots organizing work. People in Santa Barbara responded by volunteering to help speak with others, work on advocacy, and contribute time and money. The most important demonstration of success in moving people: On Election Day, Santa Barbara defeated Prop 8 by ten points. It was the only county in Southern California to vote No on 8. (Unfortunately, Let California Ring did not have the early funding needed to expand the program more widely.)

After our movement’s loss with Prop 8, Let California Ring continued its public engagement work, by 2010 expending $2.5 million to run 14 ads in 7 languages in 69 ethnic newspapers and on 42 radio stations and 40 websites. The ads featured family members from Asian-Pacific Islander Latino, and African American communities, all explaining why their family member’s marriage fit into their cultural values and tradition.

Since Let California Ring had brought Evan and Thalia to work together, Thalia moved to Freedom to Marry, bringing the insights gleaned from Let California Ring.

Deep Dive into Messaging Research & What We Learned

Thalia Zepatos, Freedom to Marry's Director of Public Engagement, worked with national and state partners to overhaul the marriage movement's messaging in 2010 and 2011.

In January 2010, Freedom to Marry charted a path to confront and solve the movement’s messaging challenges. We initiated a deep dive into previous research to find out what had worked, and what had not, and enlisted pollster Lisa Grove to analyze all existing research data from the many state campaigns – over 85 data sets. We also organized a confidential research collaborative, which we called the Marriage Research Consortium (MRC), inviting leading national and state organizations (such as the Movement Advancement Project, Basic Rights Oregon,Third Way, and GLAD ) that were also investing in marriage message research to join.

The analysis from Grove underscored what we had seen first-hand – previous messaging which focused on the “rights and benefits” of marriage and on the notion of equality and civil rights was effective with those we’d already enlisted to our cause, but was not persuading conflicted voters.

Voters who were “conflicted” on marriage often knew someone who was gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender. They wanted to be fair and supportive of LGBT people—yet they were not convinced that same-sex couples “deserved” marriage. For one thing, those voters felt that domestic partnership or civil union provided the “rights and benefits” that the gay community had been asking for. They also suspected that same-sex couples wanted to marry for “political reasons” rather than for the reasons they themselves had gotten married.

Through intensive message testing, Freedom to Marry and our national and state partners uncovered a key disconnect between the marriage movement's message and what resonated with voters.

In perhaps our biggest “A ha!” moment, we learned that many voters thought that gay couples wanted to marry to gain rights and benefits (which is actually what we’d been telling them) – but that voters saw this as a very different motivation from why they themselves would get married, i.e. for love and commitment. And over one-fifth had no idea why gay couples would want to marry.

Step by step, through our partnership with Grove, we discovered the building blocks of a new message strategy: messages had to be in sync with conflicted voters’ — and most same-sex couples’— understanding of what was central about marriage. Marriage, for these voters, was about love and commitment. To reach them and persuade them to vote in favor of marriage equality, advocates had to communicate that marriage mattered to gay and lesbian couples for the same reasons that it mattered to straight couples.

In partnership with Basic Rights Oregon, we worked on a new ad called Love and Marriage, featuring four long-term couples, two straight and two gay, talking about why marriage mattered to them. It resonated well with those who were “conflicted” on marriage (below).

Through further research, we learned that these conflicted voters responded to the invocation of shared values: some responded to the Golden Rule, others to the value of freedom. Our challenge as advocates was to model the journey from unsure to accepting for voters who were truly conflicted.

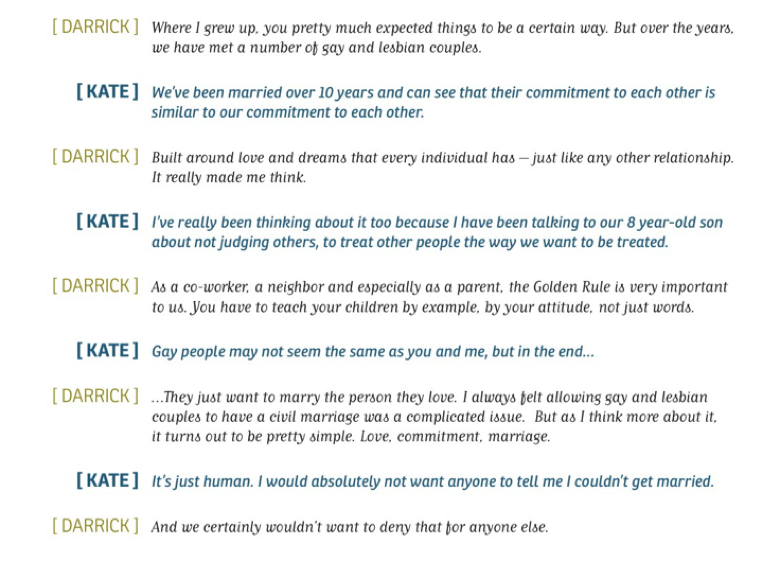

We worked alongside Basic Rights Oregon to create and test an ad called "Neighbors," featuring a real couple in this exchange:

By 2012 we were helping to create multiple ads with “Journey” stories, which showed how an individual or couple had worked through their conflicts around the idea of marriage for same-sex couples. Pollster Amy Simon focused on the concerns of people of faith – this ad aired in Washington’s successful 2012 campaign, featuring a minister and his wife describing their progression to support of their gay son and his partner. Subsequent ads in Utah (2014) and Oklahoma (2014) surfaced this same effective messaging approach in even more conservative communities.

Getting the Movement on Message: Why Marriage Matters

Once we had completed our core message research in 2011, we summarized all of these findings in a seminal movement document, “Moving Marriage Forward,” and coauthored “The Allies Guide to Talking About Marriage for Same-Sex Couples” with the Movement Advancement Project. We then initiated a national public education framework/ campaign, called Why Marriage Matters (WMM), and recruited more than 40 national and state-level partners. Offered free to these movement partners, this core public education program helped get all the players onto the same messaging. A key reason for the effectiveness of Why Marriage Matters was that it wasn’t overtly branded as a Freedom to Marry project—we thought of it as a movement message framework that was for use by everyone. By providing new materials and updates, it became the foundation for movement messaging nationwide. Through the WMM portal, we continually shared state-of-the-art research findings, personal stories, and ready-made tools like videos, graphics, speakers bureau and house party kits to reshape the national conversation on marriage and help each state build a customized marriage campaigns. [See separate memo on Why Marriage Matters for additional detail.]

Creating an Echo-Chamber of Effective Messengers

Over time we realized that, in addition to the right messages, we needed powerful messengers to help grow and amplify support. With careful analysis, we found out which messengers could be most persuasive, such as older parents speaking about their gay children and both gay and straight veterans, and we identified a broad range of other important story-tellers.

We continued to harness the power of “journey stories,” including that of President Obama. By the time Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, and Washington ended up on the November 2012 ballot, we had gained a Messenger-in-Chief. After working closely with—and pressuring—the White House, we were thrilled that President Obama came out in support of marriage for same-sex couples using the love and commitment and journey framework that was proving so effective elsewhere. In a single day, the President modeled the journey for all Americans, and gave permission to those who were most conflicted to join in support.

Freedom to Marry became a story-telling machine – we focused a great deal of time identifying real people to serve as compelling messengers and telling their stories, from military couples who were discriminated against in marriage, to seniors who face heart-wrenching impacts as they lose their life-long partner and suffer great economic harm as a result of ineligibility for Social Security survivor benefits.

Responding to Opposition Attacks

Telling the right stories with effective messengers to persuade conflicted voters was not enough, however; we also had to respond effectively to attacks. Pollster Amy Simon helped craft a powerful approach to engaging voters who expressed faith-based concerns generated by religious attack ads. We found that “two-track messaging,” keeping our positive values-based messages before voters, while adding a second track of response ads (which also invoked those key values) to rebuff our opponents’ attacks, was very effective.

We also vowed to find an answer to the scare-tactic that we saw play out so painfully in California— arguments by the anti-gay side that sought to scare voters away by misrepresenting that marriage would be taught in the schools, or claiming that young children would be harmed. Working in partnership with Third Way, our team dug through round after round of research to understand the heart of their concern.

Having done this work in advance, we were able to make sure each 2012 ballot campaign was armed with this research. When the opposition went up on TV with their predictable scare tactics, our campaigns were immediately ready with response ads that had already been extensively tested. More importantly, we made sure we never got pulled off our core message. Even as we responded to attacks, we had a two-track television plan that kept highlighting the stories of love and commitment and the core values that inspire lead voters to support the freedom to marry. Here's an example from the Mainers United for Marriage campaign from 2012:

Growing the Majority for Marriage

From 2010-2015, Freedom to Marry and our partners reshaped the national conversation on marriage around powerful and effective messages focused on love, commitment, fairness, and freedom, while highlighting new messengers and the journey stories of people in the “moveable middle.”

Initially our goal with the message work was to gain majority support. Our testing showed clearly that once we “cracked the code” on talking about marriage, the shift to values-based messaging drove exponential growth in support for marriage.

Key Lessons Learned

In addition to getting the movement on message, creating effective model ads and materials, and recruiting diverse messengers, we employed multiple approaches for engaging voters. One-on-one conversations with undecided voters were tested rigorously and proven to be especially effective. Driving a narrative focused on personal stories and the harms of denial of marriage through social media, in print and on television news kept the drumbeat going.

These are the key factors – and lessons gleaned from them – that contributed to our success in connecting with conflicted voters and building the majority for marriage from 2010-2015:

- Identify research partners who wanted to dig deep, beyond the “surface arguments” in play, in order to find the underlying causes and concerns of potential supporters. We also used non-traditional research methods to ensure that we were identifying those concerns.

- Conduct extensive message testing and development to determine how to most effectively promote our cause and combat our opponents’ most effective arguments over the airwaves.

- Invest early in public education campaigns to lay a solid foundation of support, place compelling stories in newspapers and on radio and television and enlist both every-day people and community leaders to serve as messengers. Here, see an example from the “Grandparents” ad aired in Minnesota before the launch of the political campaign:

- Recruit people to share authentic stories, including both straight allies and same-sex couples talking about why marriage mattered to them, and share stories of the personal journeys of those who had come around to support after years of inner conflict.

- Highlight unexpected allies, leading new supporters to see that they are not alone in rethinking the issue.

- Immediately push back to opposition attacks, fact-check, and call out misinformation.

- Employ targeted approaches to reach key audiences of voters—Republicans, communities of color, people of faith, and others, using community-specific approaches adjusted state-by-state.