“Our nation was founded on a bedrock principle that we are all created equal,” President Barack Obama declared just after 11:00am on Friday, June 26, 2015. “The project of each generation is to bridge the meaning of those founding words with the realities of changing times - a never-ending quest to ensure those words ring true for every single American.”

Less than an hour before, the United States Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling that the Constitution guarantees the freedom to marry to same-sex couples.

President Obama continued: “Progress on this journey often comes in small increments, sometimes two steps forward, one step back, propelled by the persistent effort of dedicated citizens. And then sometimes, there are days like this, when that slow, steady effort is rewarded with justice that arrives like a thunderbolt.”

The president’s words could not have rung out more powerfully: As he delivered his remarks, same-sex couples were at last legally marrying in Georgia, in Ohio, in Texas, in Mississippi, with city and town clerks throughout the country nationwide preparing to issue marriage licenses to all loving couples in the coming hours and days. The immediate, tangible impact was overwhelming.

No union is more profound than marriage, for it embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family. … [These men and women] ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The Constitution grants them that right.

The Supreme Court of the United States, Obergefell v. Hodges, June 26, 2015

Members of the Freedom to Marry team celebrate in New York City following the U.S. Supreme Court victory in Obergefell v. Hodges.

Our nation will remember June 26, 2015 as the day that Love Won – a day where all of America could proudly celebrate a triumphant transformation. The pathway to this final victory stretched back for miles and years, drawing on those “small increments” and the “countless, often anonymous heroes” that the President acknowledged. The decades-long journey required the effort, energy, talents, and passion of a movement and millions of people – as well as a national strategy and a campaign to drive that strategy every single day. It required a dream, and it depended on a national conversation among all Americans about who gay and lesbian people are – and why marriage matters.

But how did we get here? How did gay people go from being an oppressed minority, whose love was denied and scorned, to a group that claimed the freedom to marry and at last won respect, dignity, and equality for their love and for their families? This is the story of the movement that transformed a nation, the strategy that movement followed, and the campaign that drove that strategy to victory: Freedom to Marry.

Chapter 1: Pioneering the Marriage Movement

The Early Years (1970s-1983)

Richard Baker and James Michael McConnell were among the early pioneers who sought the freedom to marry in court in the 1970s and 1980s.

Within living memory, gay people in America were a despised, oppressed minority. Same-sex couples’ love was scorned, summarily rejected by enormous swaths of the country, feared, deemed “immoral” and “pathological,” and made illegal. The notion of same-sex couples lawfully marrying was unthinkable - and early pioneers who bravely stepped forward to claim the freedom to marry were met with derision and venom.

From the dawn of the modern LGBT movement, in the immediate aftermath of Stonewall in 1969, same-sex couples in several states filed legal challenges seeking the freedom to marry. Courts of Appeals in Washington and Kentucky dismissed cases, with the Kentucky judge writing, “What they propose is not a marriage.” In Colorado an American was forced to choose between his country and the love of his life, an Australian man, when their legal request for a spousal visa was denied by the Immigration & Naturalization Service which literally wrote, on government letterhead: “You have failed to establish that a bona fide marital relationship can exist between two faggots.” And in 1972, a Minnesota couple took their attempt to marry all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which summarily turned down the case “for want of a substantial federal question.”

The country wasn’t ready, and the cases were rubber-stamped away. Too many Americans were unfamiliar with gay and lesbian people, and following these cases – beginning in 1972 with Maryland – several states passed statutes explicitly banning marriage between same-sex couples.

Evan Wolfson wrote one of the earliest analyses of the freedom to marry for same-sex couples in 1983 with his Harvard Law School thesis.

In 1983 during his third year at Harvard Law School, Evan Wolfson wrote his thesis on the freedom to marry, asserting gay people’s claim to this constitutional right. The 140-page thesis, written at a time when same-sex couples had no country- or state-level recognition anywhere in the world (let alone marriage), explained that denying one class of people access to marriage was state-sponsored discrimination that required correction.

Wolfson, now often referred to as the “godfather” and “architect” of the marriage movement, believed that by claiming the resonant vocabulary of marriage (love, commitment, connectedness, and freedom), same-sex couples could transform the country’s understanding of who gay people were and, as a result, why exclusion and discrimination are wrong. The fight for marriage would function as a powerful engine to change hearts and minds, which would provide impetus to enact legal protections for LGBT people even beyond including same-sex couples in marriage.

Wolfson’s pioneering vision in this paper later served as the inspiration for the national strategy to win marriage for same-sex couples, anticipated the case for ending marriage discrimination that would prevail in the courts of law and the court of public opinion, and framed the national campaign behind the strategy that won, Freedom to Marry.

Chapter 2: Launching the Movement

The Global Marriage Movement Begins in Hawaii (1993-1996)

Same-sex couples weathered many challenges in these early years following the failed first wave of marriage litigation, most tragically the cataclysm of HIV/AIDS, which shattered the silence about gay people’s lives. The epidemic forced non-gay people to see gay people, not just as stereotypes, but as human beings who love, grieve, sacrifice, and fight back. And it prompted gay people to better understand how the denial of marriage harmed their ability to care for each other. It transformed the movement from seeking to be let alone – "don’t harass us, don’t persecute us, don’t attack us" – to seeking to be let in.

As the LGBT community worked to prevail against the epidemic and escalating discrimination, activists grappled over what the movement’s priorities should be going forward. Some activists presented ideological resistance to marriage entirely, asserting that working to win marriage was in itself a flawed goal – arguing that marriage is a patriarchal institution that should be avoided and that LGBT people should chart their own path for sexual liberation and relationships rather than embrace marriage. Others had strategic concerns, declaring that the nation would never be ready to allow same-sex couples to wed and that the pursuit would harm the community’s ability to prevail on other, seemingly more likely, gains. There were fierce debates, with Evan Wolfson – then at Lambda Legal – pressing for an affirmative strategy on claiming marriage. Wolfson’s call for action was joined by a handful of others, including the then-editor of The New Republic Andrew Sullivan.

Gay marriage is not a radical step. It avoids the mess of domestic partnership; it is humane; it is conservative in the best sense of the word.

Andrew Sullivan, “Here Comes the Groom.”

In 1993, a game-changing victory for the freedom to marry, in Hawaii, shifted the debate permanently.

With the advent of a second wave of marriage litigation nearly 20 years after the first, several same-sex couples went to court in 1990 seeking the freedom to marry, represented by non-gay attorney Dan Foley, who brought in Evan Wolfson as his co-counsel. In 1993 the Hawaii Supreme Court declared marriage discrimination presumptively unconstitutional for the first time in history, and the subsequent historic trial in 1996 resulted in the world’s first-ever ruling that same-sex couples should have the freedom to marry.

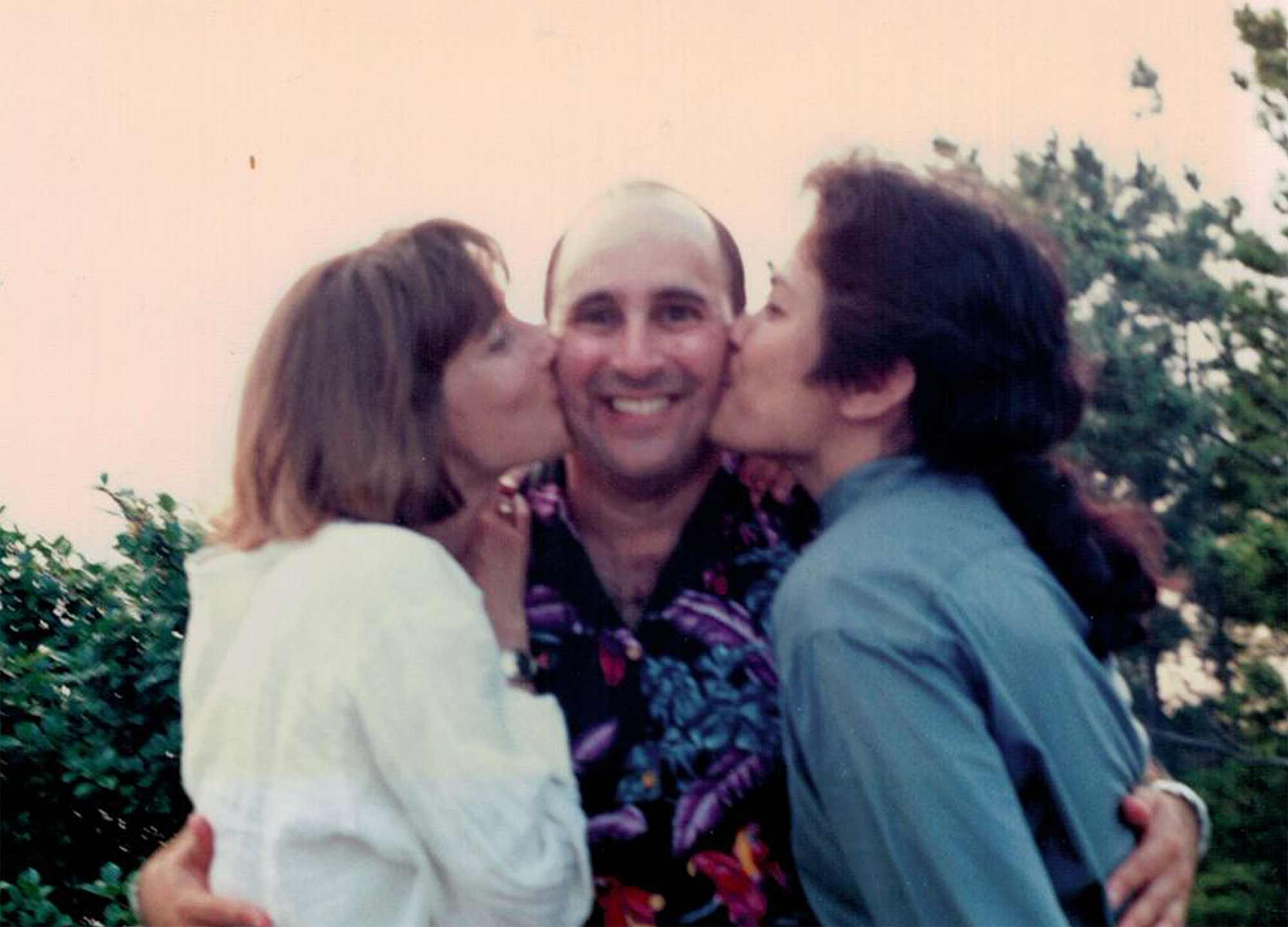

Evan with plaintiffs Ninia Baehr and Genora Dancel in Hawaii case, 1993.

The Hawaii victory, put on hold while opponents appealed, showed that what had been an abstract notion could become real. With the prospect of the freedom to marry now a real possibility in the United States, anti-marriage opponents nationwide pushed exhaustively to block pro-marriage advances. Most painfully, in Hawaii, before the Hawaii Supreme Court could even hear the appeal, anti-gay forces poured millions of dollars into a fear-based campaign, stampeding voters into passing a constitutional amendment that snatched away the freedom to marry shimmering within reach. A similar turn of events – a lower court marriage win followed by a constitutional amendment outright restricting marriage to different-sex couples – followed in Alaska, while another case, in DC, lost on appeal. By 1998, many state legislatures had adopted updated statutes restricting marriage to different-sex couples and in some cases rolling back what little legal protections – health coverage at work, bereavement leave – gay people had achieved piecemeal over decades.

Opponents of the freedom to marry didn’t stop at the state level. As a 1996 election-year tactic, anti-gay activists and members of Congress successfully pushed through the so-called “Defense of Marriage Act” (DOMA), a preemptive measure declaring that even if states began issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples, these marriages would be denied all federal respect, and same-sex couples would not be eligible for any of the 1,100+ protections and responsibilities that marriage triggers at the federal level. The attack sought to shut down the debate before Americans even had a chance to consider the question of marriage for same-sex couples. In September 1996 – even as the marriage trial was underway in Hawaii – the bill was signed into law by President Bill Clinton following its passage in the House by a 342-67 vote and in the Senate by an 85-14 vote.

The United States Congress passed the so-called Defense of Marriage Act in 1996 to preemptively deny respect to marriages between same-sex couples.

In spite of the pushback, the Hawaii victory offered hope to many gays and lesbians throughout the country that victory could be achieved and that marriage was a pursuit worth fighting for. Wolfson, now marriage project director for Lambda Legal, organized national LGBT groups to meet on a regular basis to enhance efforts to achieve the freedom to marry. They came together around a single statement of support, the Marriage Resolution, declaring a commitment to fighting for the freedom to marry.

Wolfson took to the road speaking to groups small and large in every part of the country to encourage them endorse the “Marriage Resolution,” enlisting same-sex couples eager to marry, activists ready to fight, and non-gay allies who recognized this important moment in the country’s history (some even took to calling Wolfson the “Paul Revere of marriage” as he traveled the country telling people that the freedom to marry is coming). With his recurrent mantra, “there is no marriage without engagement,” Wolfson preached that winning would require hard work and wouldn’t be happen overnight. Wolfson encouraged grassroots groups to come together to do the public education necessary to advance the cause, and small groups sprung up, including in Massachusetts and New York.

As the Hawaii case moved forward, the movement opened a new front in the marriage fight with litigation filed in Vermont by civil rights attorney Mary Bonauto of Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders and local attorneys Beth Robinson and Susan Murray. In 1999, the Vermont Supreme Court ruled that the state must afford same-sex couples the same “benefits and protections” that different-sex couples can access through marriage, but gave the legislature the right to determine whether to open marriage to same-sex couples or create a new status that provided the same protections and benefits at the state level. The legislature and governor preemptively took marriage off the table, and intense debate ensued around whether to create the new status of civil union or to adopt a constitutional amendment undoing the court’s ruling. In the end, civil union prevailed, with the marriage movement hailing this as an important – though incomplete – step forward. Even though the legislature had withheld marriage and offered only civil union, the anti-gay resistance was severe, and under the banner of “Take Back Vermont,” opponents mounted an effort that unseated sixteen lawmakers who had voted for civil union.

Chapter 3: Creating Freedom to Marry

The National Campaign (2003)

After the enactment of the federal “Defense of Marriage Act” (DOMA) adding a new level of prospective federal marriage discrimination to the marriage discrimination already in all 50 states, the snatching away of the freedom to marry win in Hawaii by a state constitutional amendment ballot-measure, and the unsatisfying securing of civil union, though not marriage itself, in Vermont, Evan Wolfson decided that in order to win the freedom to marry, the movement needed a new campaign organization with a singular focus to drive a national strategy forward.

The passage of DOMA demonstrated the need for more thoroughly educating the American people and their representatives about who gay people are and what marriage brings to them and their families, intangibly as well as tangibly. The Hawaii constitutional amendment showed that a win in court was useless if the win – and the joy it brought afterward – couldn’t be defended and sustained. And the establishment of civil union in lieu of marriage in Vermont confirmed the idea that educating on why marriage matters was crucial.

In 2000, leaders of the Evelyn & Walter Haas Jr. Fund approached Wolfson seeking advice about how they could best support work to advance rights and dignity for gay people.

Wolfson urged them to support a sustained affirmative campaign to drive a national strategy and win the freedom to marry. The campaign Wolfson called for would bring together key organizations and bring in new ones, galvanize a movement and millions of conversations, and develop and drive tactics to win.

Haas Jr., a highly respected, non-gay foundation, took the leap and made a $2.5 million challenge grant investment in 2001 – then the largest foundation award in the history of the gay rights movement. The grant seeded Freedom to Marry, the campaign to win marriage nationwide, which officially launched in 2003.

In a September 2001 rallying cry laying out a blueprint for a sustained, affirmative marriage campaign, Wolfson wrote, “It is time for a peacetime campaign to win the freedom to marry. We cannot win equality by focusing just on one court case or the next legislative battle – or by lurching from crisis to crisis. Rather, like every other successful civil rights movement, we must see our struggle as long-term and must set affirmative goals, marshal sustained strategies and concerted efforts, and enlist new allies and new resources.”

Shimmering within our reach is a legal structure of respect, inclusion, equality, and enlarged possibilities, including the freedom to marry. Let us build the new approach, partnership, tools, and entities that can reach the middle and bring it all home.

Evan Wolfson, "All Together Now: A Blueprint for the Movement," September 2001

Drawing from other civil rights movements and battles, as well as the law of marriage in the United States, the campaign Wolfson envisioned would drive a clear strategy: The movement would win the freedom to marry nationwide when one of the country’s two national actors, Congress or the U.S. Supreme Court (most likely the Court), brought the country to national resolution. To create the climate that would impel that national resolution, the campaign would work to build a critical mass of states where same-sex couples could marry and a critical mass of public support.

The Freedom to Marry strategy proposed that marriage advocates didn’t have to win every state, but they had to win enough states – and not every American had to be persuaded to support the freedom to marry, but enough Americans needed to be supportive to empower, embolden, and impel the Supreme Court, or possibly Congress, to act.

This national strategy – which Freedom to Marry called the Roadmap to Victory and spelled out publicly and often – was the strategy responsible for the movement’s long climb to success, building from 27% support among the American people (at the time of the Hawaii trial in 1996) to 63% (in 2015), from zero states to 37 states when the Supreme Court heard oral arguments and finally ruled.

Key organizations and funders embraced the Freedom to Marry strategy and brought crucial pieces to the table. The strategy and campaign catalyzed nationwide action and a true movement of engagement, creating the powerful momentum and progress that encouraged the Supreme Court Justices in June 2015 to finish the job and strike down marriage discrimination once and for all.

Chapter 4: Winning the First State

First Marriage State in Massachusetts (2003-2004)

Supporters celebrate victory for the freedom to marry in Massachusetts.

The top objective of the marriage movement in the first few years of the new millennium was simple but not at all easy: Win and hold the freedom to marry in one state – anywhere.

In 2001, Mary Bonauto and the Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders team filed Goodridge v. Department of Public Health, seeking the freedom to marry in Massachusetts and kicking off a multi-year court battle, while Wolfson continued his work building Freedom to Marry and encouraging local LGBT advocates to organize around marriage work in their own communities and states. Many of the established movement groups were reluctant - but Wolfson’s call to arms inspired individuals throughout the country to form their own marriage advocacy groups, such as the Massachusetts Freedom to Marry Coalition. As Bonauto and GLAD made their case to the Massachusetts courts, the Massachusetts Freedom to Marry Coalition engaged with LGBT community and potential non-gay allies in the legislature, in houses of worship and elsewhere, explaining why marriage matters to all loving couples.

The year 2003, when Freedom to Marry officially launched, saw a flurry of significant advances for gay and lesbian people: Neighbors to the North in Ontario, Canada began marrying following a court victory; couples celebrated their second wedding anniversaries in the Netherlands; and the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the freedom of intimate conduct, including for gay people, in the landmark Lawrence v. Texas, litigated by Lambda Legal. Justice Antonin Scalia summed up the impact of these advances in his fiery dissent in Lawrence, where he said, “This reasoning leaves on pretty shaky grounds state laws limiting marriage to opposite-sex couples.”

Justice Scalia’s lament proved prophetic when, on November 18, 2003, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in the Goodridge case. In 180 days, the freedom to marry for same-sex couples would be a reality for the first time in American history.

Within minutes of the Goodridge decision, marriage opponents vowed to reverse it, bent on standing in the way of committed couples. With the freedom to marry finally in reach, it was more important than ever for marriage supporters to double down and stave off the kind of state constitutional amendment that had forestalled ultimate victory in Hawaii. Advocates formed MassEquality--a coalition made up of the Massachusetts Freedom to Marry Coalition, the ACLU of Massachusetts, the Massachusetts Gay & Lesbian Political Caucus, GLAD, and other organizations as well as key funders — to defend the Goodridge win.

Headed by seasoned campaign operatives Marty Rouse and later Marc Solomon (who would go on to become Freedom to Marry’s National Campaign Director), MassEquality fought back against the opposition with a grassroots campaign on the ground, a targeted lobbying campaign in the statehouse, and strategic work re-electing pro-equality lawmakers and defeating a few who were opposed. Everyone understood how critical this work was: Marriage in Massachusetts was a flame that the movement had succeeded in lighting - and the flame was still glowing, still illuminated, despite constant efforts to snuff it out. Protecting the flame was vital.

MassEquality advocates fired on all cylinders, pioneering much of the vital field, organizing, and storytelling work that would go on to define the marriage movement.

The breakthrough in Massachusetts also gave new energy to advocates nationwide. In early 2004, San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom directed clerks to begin issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples, and similar developments occurred in Sandoval County, New Mexico; New Paltz, New York; and Multnomah County, Oregon. Although these actions were quickly halted and the legal validity of the marriage licenses was called into question, they showcased the intense demand among same-sex couples for the freedom to marry and started many Americans on their journeys toward understanding same-sex couples.

When it came to defending Massachusetts, of course, the movement’s losses in Hawaii and Vermont, as well as on Capitol Hill, left no doubt: The fight would be tough. Opponents of the freedom to marry – then-Governor of Massachusetts Mitt Romney, the Catholic Church, the right-wing anti-gay industry, and even President George W. Bush, scrambled to subvert the Goodridge decision. Leading Democrats in the state—the Senate President, the House Speaker, the Attorney General, and even Senator John Kerry—were also opposed. But with national support mobilized by Freedom to Marry and key funders such as Colorado’s Tim Gill, marriage supporters kept fighting, using smart organizing and innovative campaign strategies to build a powerful grassroots movement while GLAD swatted down numerous legal challenges that attempted to delay the first weddings in the state.

Just before midnight on May 17, 2004 – three decades after the very first legal case from a same-sex couple seeking marriage – Mary Bonauto took the stage at a reception at Cambridge City Hall, where dozens of same-sex couples were ready to say “I do.” Bonauto invoked the words of Dr. Martin Luther King as she looked out on the crowd: “The arc of the moral universe is long but bends toward justice.” She paused. “In a few minutes, it’s going to take a sharp turn.” In the hours that followed, hundreds of couples married. It was the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education – “civil rights karma,” as Evan Wolfson called it.

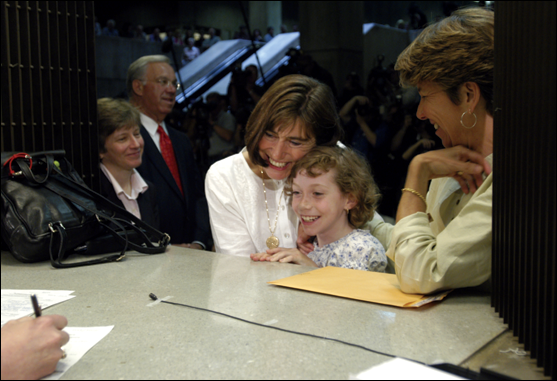

Julie and Hillary Goodridge, named plaintiffs in the Massachuestts victory, at last marry with their daughter and attorney Mary Bonauto looking on.

Over the next two years, MassEquality activists fired on all cylinders. They deflected blow after blow from forces who wanted to put a stop to the freedom to marry. They mobilized thousands of supporters to engage in real conversations with state legislators on the importance of voting NO on any anti-marriage constitutional amendment. They threw their support and energy behind incumbent legislators who had voted to protect the freedom to marry. And on June 14, 2007, their unrelenting efforts prevailed: With a vital boost from Governor Deval Patrick and changes of heart from many legislators, advocates were able to get the legislature to vote down the constitutional amendment that would have repealed the freedom to marry. What’s more – of the 195 pro-equality incumbent reelection races over the course of 2004 and 2006 election cycles, pro-equality candidates won every one, beginning to change the notion that a pro-equality vote was politically risky.

The first freedom to marry state was won and held.

Marc Solomon, a key leader in the Massachusetts fight (and later National Campaign Director of Freedom to Marry, thanks Gov. Deval Patrick for his sustained advocacy in defending the freedom to marry in MA.

Chapter 5: Pursuing the 2nd State

Looking Forward While Pushing Through Defeats (2004-2008)

While Marc Solomon and the MassEquality team focused on protecting the freedom to marry in Massachusetts, national leaders faced significant challenges in mid-2000s fighting back against state and federal anti-marriage constitutional amendments while seeking to secure victory in a second state. In 2004, anti-marriage constitutional amendments were on the ballot in thirteen different states, an insidious maneuver by Karl Rove and the national Republican Party to increase conservative turnout in the 2004 election. As the election drew closer and it appeared nearly certain that all of the anti-gay amendments would pass, some in the LGBT movement flinched, expressing concern about pushing forward on the marriage work. That wavering increased after the election.

Others, however, pushed onward, opposed to slowing down the push for marriage. The movement had already won its first victory – and for the first time, Americans were seeing same-sex couples marry, these leaders explained. If funders and organizations put on the brakes now, momentum could teeter, and the movement could become stagnant.

Evan Wolfson spoke to these concerns in an address at the Lavender Law Conference, just before Election Day. He placed the movement’s struggles in context: Any year where you lose ballot measures in states that don’t have marriage yet break through to win the freedom to marry in the country’s first state itself is actually a winning year, Wolfson argued. He offered lessons from history on the “Scary Work of Winning,” and lesson one, he said, is “Wins trump losses,” because the power of the win – the changed hearts and minds brought on by the win – would enable the movement to keep organizing and educating and overcome the loss. Lesson two, Wolfson said, is that even when the movement cannot win on the opposition’s timeline, it should seek to “lose forward” - use each fight to grow support for the next inevitable battle. Winning the war, he explained, can entail losing many battles and yet make the most of the fight with smart education and constant work to spark conversations, grow support, and keep going.

On Election Day 2004, marriage supporters lost every one of the ballot fights. And President George W. Bush, who widely discussed his support for amending the federal Constitution to ban same-sex couples from marrying, won election to a second term. Several prominent Democrats blamed the year’s losses on the push for the freedom to marry, and that narrative unfortunately took hold in certain circles in spite of the fact that political scientists later concluded that wasn’t the case. Certain leading LGBT groups suggested slowing down the campaign to win marriage.

Following the elections, Wolfson helped organize leaders in the LGBT movement to recommit to the fight. The problem wasn’t pursuing marriage; it was the lack of a well-resourced, coordinated campaign to prevail. In 2005, more than a dozen leaders, including Wolfson, Mary Bonauto, and Matt Coles of the American Civil Liberties Union, came together to rearticulate the strategy, this time with significantly more detail, and renew the call for an expanded campaign. The outcome of many discussions was a concept paper, with Coles the chief drafter, called “Winning Marriage: What We Need to Do.”

We need to have a coordinated, national campaign, building on the work that is already being done, but going way beyond it to take on the comprehensive national work that is not being done today but that is crucial to success. This must be a thoroughly professional campaign, professionally staffed and run, with the enthusiastic support of the organizations working on marriage today.

Matt Coles, in 2005 Concept Paper, "Winning Marriage: What We Need to Do"

The concept paper again called for a robust public education campaign on marriage and outlined how, over the next decade-plus, the movement could win the freedom to marry through the strategy of building a critical mass of states and public support to create the climate for litigation in the Supreme Court. Explaining what that critical mass might look like, marriage proponents invited stakeholders to imagine that, before bringing a case to the Supreme Court, the movement had won marriage in ten states, secured civil union or ‘all but marriage’ status in ten, achieved limited protections for same-sex couples in an additional ten, and substantially grown support for the freedom to marry in the remaining twenty. The concept paper, which became known as the “10-10-10-20” or “2020 Vision,” was another crucial turning point for the movement, signed by every major LGBT group and helping stamp out discussions within movement leadership about backpedaling on marriage.

In 2005, for the first time ever in the United States, a state legislature approved marriage legislation – a bill in California shepherded by Equality California – but Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger vetoed it (and a subsequent marriage bill in 2007). Advances through civil union and domestic partnership moved forward in Connecticut, Washington, Maryland, California. Important public education campaigns surged in New York and across New England.

The mid-2000s were often marked by losses for the marriage movement, but supporters rallied, regrouped and worked harder than ever to push forward.

There were also more losses: Anti-gay groups stampeded through anti-marriage constitutional amendments in another eight states in 2006, and, most painfully, the movement continued to struggle to win State No. 2. Over a six-month period in 2006 and 2007, high courts in four states – New York, Washington, Maryland, and New Jersey – ruled against the freedom to marry.

Finally, following a relatively large-scale public education and organizing effort that sought to lay the groundwork for court victories and legislative successes, advocates succeeded in winning the freedom to marry in California in May 2008. In a case brought by the ACLU, Lambda Legal, and the National Center for Lesbian Rights, the California Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional to deny marriage to same-sex couples. Thousands of loving, committed couples from across the country flocked to California over the next few months to say “I do.”

The No on 8 campaign to block repeal of the freedom to marry suffered a tough loss in November 2008, igniting a years-long process to win back California.

On November 4, 2008, however, the joy and victory were snatched away when Proposition 8—another anti-gay constitutional amendment—was narrowly approved by a 52% to 48% margin at the ballot after an emotionally draining and financially taxing campaign, unjustly halting the California weddings and igniting a years-long process to win back the state.

Fortunately, the movement had, as Evan Wolfson put it, “brought a spare”: A case from Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders won the freedom to marry in Connecticut in October 2008, and even in spite of the loss of California, the year ended with the long-sought second state in hand – plus a fired-up community motivated by their anger about Proposition 8 and inspired with the hope of a better climate reflected in the historic election of a new president, Barack Obama.

Chapter 6: Rebounding and Transforming Freedom to Marry

Strengthening the Capacity & Infrastructure of the Central Campaign (2009-2010)

The ballot loss in California, which stripped same-sex couples of the freedom to marry, served as an important wake-up call for Americans.

Without a doubt, Proposition 8 was a painful disappointment, and in California in particular, it caused a lot of turmoil and anger within the movement. But despite the blow, Prop 8 was also a wake-up call for the gay people who had sat on the sidelines and counted on “inevitable” victory. Non-gay people, too, saw their consciences shocked by the reality that a narrow vote could strip same-sex couples of a freedom that they already held in their hands. The rebound from Prop 8 gave new energy to the campaign, with many more across the country ready to mobilize and fight to win the freedom to marry.

Among the crucial players joining Freedom to Marry in upping the game was the Gill Action Fund, launched by entrepreneur and donor Tim Gill after the passage of the 13 constitutional amendments in 2004. The Gill Action Fund built a team of political strategists and helped focus LGBT funders to invest their donations into advocacy campaigns and candidates that would advance LGBT rights in the states. While most of the movement organizations to this point were limited in the political work they could do, Gill Action provided needed heft in the arenas of lobbying and electoral work, as well as political fundraising. Gill Action partnered with Freedom to Marry and movement colleagues undaunted by the loss in California, focusing now on creating the climate to win in the next wave of targeted states.

Funders also stepped up to the challenge, with several banding together to support the Freedom to Marry strategy through a “Civil Marriage Collaborative,” supplying more resources to support the needed state-based efforts. For the next 11 years, the Civil Marriage Collaborative worked diligently to support a wide array of focused and multi-dimensional public education efforts to change hearts and minds, working closely with grantee partners and collaborating with key national stakeholders to maximize the effectiveness of the philanthropic and overal strategic work.

The movement’s crucial legal arm – the ACLU, GLAD, Lambda Legal, and the National Center for Lesbian Rights – mounted court challenges in several more states. And Freedom to Marry continued to court and enlist allies from labor; religious communities and denominations; the African-American, Latino, and Asian-American civil rights organizations; and the business world, while working hard to amp up and drive a national narrative in the media.

While California reeled from the pain of the loss, the bulk of the marriage movement kept working the Freedom to Marry strategy and delivered in 2009 the winningest year to that point, racking up more states and climbing toward a national majority in favor of the freedom to marry. State and national groups worked together throughout New England – with a focus on Vermont, Maine and New Hampshire – to build strong pro-marriage public education, campaign and electoral efforts. The teamwork and tenacity resulted in real victories: In Vermont, advocates persuaded the legislature to push past civil union and embrace the freedom to marry, even overriding the Governor’s veto for the first marriage win in a legislature. The Iowa Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favor of marriage for same-sex couples in a Lambda Legal case, and on-the-ground advocates along with national partners were able to successfully hold the win, protect crucial lawmakers, and stave off legislative threats of a constitutional amendment. Maine and later New Hampshire enacted the freedom to marry through the legislature and the signature of the Governor. The City Council in Washington, D.C. passed a bill bringing the freedom to marry to the nation’s capital.

Back in California, groups like Equality California, Lambda Legal, and the National Center for Lesbian Rights worked to regroup, pull together constructive public education efforts, and build toward a “do over” ballot campaign to restore the freedom to marry. Meanwhile, in May of 2009, Rob Reiner, aided by Chad Griffin and screenwriter Dustin Lance Black, brought together former George W. Bush Solicitor General Ted Olson and Democratic attorney David Boies to mount a challenge to Proposition 8 in federal court, Perry v. Schwarzenegger. They created the American Foundation for Equal Rights to fundraise and do public relations around their case, declaring their intent to seek a national marriage ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court as soon as possible. The District Court judge in the case instead ordered a careful timeline and a full trial, which, like the Hawaii trial 14 years earlier, provided a strong educational tool for many Americans while opening the door to significant future momentum toward an eventual Supreme Court victory.

As Freedom to Marry and its partners moved forward on the national strategy, the states weren’t the only battlegrounds: Beginning in 2008, movement colleagues ramped up work to overturn the so-called Defense of Marriage Act. GLAD first filed suit in federal court, bringing forward the stories of married couples and surviving spouses from Massachusetts who had suffered tangible harms as a result of DOMA. Others followed, including attorney Roberta Kaplan – in partnership with the ACLU – filing suit on behalf of Edie Windsor. In addition to elevating the stories of the harms of DOMA, Freedom to Marry helped craft a DOMA repeal bill in Congress called the Respect for Marriage Act, and went to work enlisting cosponsors. The aim of taking down DOMA was part of the movement strategy – the Roadmap to Victory – which urged work on three tracks to set the stage for bringing a case to the Supreme Court at the right time.

Then, another stumble: Marriage opponents succeeded in overturning the freedom to marry in Maine with the passage of Question 1 at the ballot.

The ballot losses in Maine and California, coupled with Barack Obama’s victory as president (see next chapter) – and the urgency that emerged from the Prop 8 wake-up call – underscored the urgency of strengthening the central campaign in order to be able to learn how to overcome persistent barriers, fill in the gaps, and drive faster to the goal of a critical mass of states and support as the prerequisite for the Supreme Court win. At the request now of key movement colleagues, funders, and other stakeholders, Freedom to Marry seized the moment to morph from an internal movement strategy center and catalyst and instead itself become the truly national campaign that the movement required. “The cobbled-together approach pursued so far by the marriage movement is not sufficient for today’s opportunities and challenges,” Wolfson wrote in a concept paper proposing the bulked up campaign.

The moment requires a stronger national capacity and galvanizing brand – a transformed Freedom to Marry – with the expertise, resources, and infrastructure to be able to move nimbly yet consistently to marshal and channel messages, messengers, people, and resources to serve the needs that exist at the state and national level, for both the vital state-by-state and increasingly doable federal work.

Evan Wolfson, in 2009 Concept Paper on importance of strengthening Freedom to Marry

After the fits and starts of the 1990s and 2000s, national movement funders and partner organizations were now ready to buy into Wolfson’s vision for Freedom to Marry, seeing that the existing ad hoc and coalition efforts were insufficient to capitalize on the momentum and drive towards nationwide victory most rapidly. Wolfson set about assembling a team that would provide the needed campaign expertise.

One of Wolfson’s first calls was to Marc Solomon, who worked so skillfully to defend marriage in Massachusetts and later assembled a team of operatives in California to rebound from Prop 8. Wolfson asked Solomon to come to Freedom to Marry as national campaign director, recruiting new staff and shaping programs to fulfill the Freedom to Marry strategy. Wolfson also enlisted Thalia Zepatos, a campaign expert and movement veteran to guide public engagement strategy, with a particular focus on retooling the messaging (See more on the messaging overhaul here). To grow support federally for repealing DOMA and built support with national elites for marriage, Freedom to Marry opened a federal office in Washington, DC, staffed by lobbying veteran Jo Deutsch. Along with digital lead Michael Crawford and political and communications strategist Sean Eldridge, Freedom to Marry could now itself do what was needed, rather than have to cajole other organizations to step up. Freedom to Marry immediately redoubled its work to drive long-term public education and messaging work; build state campaigns in priority states to achieve victory; organize conservatives, mayors, and other political leaders; and secure support on Capitol Hill and within the DC Beltway.

The Freedom to Marry team in 2015, including (L-R) Marc Solomon, Scott Davenport, Thalia Zepatos, Michael Crawford, Evan Wolfson, Jo Deutsch, Kevin Nix, Juan Barajas, and Richard Carlbom.

By 2010, the freedom to marry had become, without a doubt, a multi-faceted national conversation that invited participation from millions of Americans and action from decision-makers coast to coast. The power of that conversation strategy became clearer than ever on August 2010, when a national poll tracked, for the very first time, majority support for the freedom to marry. The nation was moving forward, and Freedom to Marry was dedicated to moving it forward as quickly and strategically as possible.

Chapter 7: Shifting the Political Center of Gravity

Winning Marriage in New York (2011)

The newly expanded Freedom to Marry team – which increased its budget seven-fold to more than $13 million and grew to a roster of more than 30 between 2010 and 2014 – was quickly put to the test. With the increased capacity, Freedom to Marry sought to continue building momentum for marriage by winning more states. In 2011 goals were set for aggressive campaigns in Rhode Island, Maryland, and New York – and after the first two campaigns hit rough patches, victory in New York became a crucial focal point.

Governor Andrew Cuomo signed the freedom to marry into law in June 2011 after months of strong leadership on the bill.

For years, marriage supporters had scoped out New York as an early battleground. In 2009, a marriage bill came to a vote in the Legislature, but the vote in the Senate failed in the eleventh hour, and marriage supporters devised a fierce electoral strategy to demonstrate to New York lawmakers that our community was serious about holding electeds accountable. The Fight Back New York political action committee ousted three anti-marriage incumbents and replaced them with strong supporters.

In 2010, Andrew Cuomo was elected Governor of the state, and from Day 1, he set passing a marriage bill as one of his administration's top priorities.

I don’t want to be the governor who just proposes marriage equality. I don’t want to be the governor who lobbies for marriage equality. I don’t want to be the governor who fights for marriage equality. I want to be the governor who signs the law that makes equality a reality in the state of New York.

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, October 14, 2010

Freedom to Marry – headquartered in New York City – was ready for the fight, realizing how dramatically a win in the nation’s third largest state would shift the political center of gravity: A victory in New York would double the number of Americans living in a state with the freedom to marry, and the state’s role as a political and cultural leader made it a powerful megaphone. Plus, with a new Republican-led Senate, the bipartisan nature of the win would open the door for GOP electeds in other states to support marriage for all.

Since the 2009 loss, the Gill Action Fund along with the Empire State Pride Agenda had been working hard to grow support in Albany. Now, with the 2011 legislative session underway, it was clear a nimble, robust, and coordinated campaign was vital– so Freedom to Marry partnered with the Empire State Pride Agenda and the Human Rights Campaign to build New Yorkers United for Marriage, with the Gill Action Fund a crucial behind-the-scenes player lending political heft. Freedom to Marry later replicated this successful coalition campaign model in multiple states in succeeding years.

Over the next few months, the New Yorkers United players swung for the fences. The campaign brought on a Republican dream team of consultants, (with funding and guidance from Republican donor Paul Singer), bulked up on communications and paid media experts, and enlisted support from top Wall Street executives.

The work surged – but days before the legislative session was set to end, the votes weren’t yet there to pass the bill. Even as the last day of the session arrived and more votes were secured, it was unclear whether the Republican leadership would bring the bill to a vote. Governor Cuomo refused to take no for an answer – and just before midnight on June 24, 2011, the New York Senate approved the freedom to marry, with four Republican Senators joining all but one Democrat.

The Republican Senators were in good company with other prominent conservatives experiencing changes of heart on the question of whether same-sex couples should have the freedom to marry. Former Vice President Dick Cheney famously indicated his support, declaring, “Freedom means freedom for everyone.” Former Georgia Congressman Bob Barr, a chief drafter of DOMA and virulent opponent of LGBT equality, voiced his opposition to DOMA and support for the freedom to marry. Ken Mehlman, President Bush’s Campaign Manager and former chairman of the Republican National Committee, came out as gay and began aggressively organizing to win the freedom to marry. Prominent Republicans like Paul Singer and Margaret Hoover enlisted financial backers. Ted Olson made inroads in court fighting against Proposition 8 and in print, with a Newsweek cover story called “The Conservative Case for Gay Marriage.” Right-of-center support was higher than ever.

Two days after the New York vote marked the 42nd annual New York City LGBT Pride March. An estimated two million people surged through the streets of Manhattan, ecstatic to celebrate the freedom to marry. Near the front of the parade route was Governor Cuomo flanked by NYC Speaker Christine Quinn and her wife Kim Catullo; and just behind was the New Yorkers United for Marriage contingent, waving signs that shouted, “Promise Made, Promise Kept.”

The New Yorkers United for Marriage team celebrating in New York City Pride, 2011

Chapter 8: Securing Support of the President and the Democratic Party

Modeling National Support with the "Messenger-in-Chief" (2012)

One of Freedom to Marry's primary goals in 2012 was to encourage President Barack Obama to announce support for the freedom to marry, a goal ultimately achieved through incredible pressure on the president, including the pressure sparked by the "Democrats: Say I Do" campaign.

Heading into 2012, Freedom to Marry set two primary (and challenging) goals for the year: First, to persuade President Barack Obama to publicly support the freedom to marry, and then, to finally break the movement’s decade-long ballot-measure losing streak.

In running for president, Barack Obama opposed the freedom to marry while supporting civil union and calling for the full repeal of DOMA. This represented a dramatic change from his predecessor, George W. Bush, but Freedom to Marry was determined to get President Obama all the way to full support, even though some in the movement urged holding off until after the election.

Freedom to Marry went to work, making the case early and often, deploying Evan Wolfson to press the case directly in repeated meetings with senior members of the administration; mounting a forceful digital campaign its members – along with a raft of celebrities and leaders – to weigh in; and enlisting influential messengers to deliver political advice to key White House, Department of Justice, and campaign decision-makers. The work intensified after Obama signaled his openness to a shift, telling AmericaBlog in a 2010 interview that he was “evolving” on the issue.

In fact, Freedom to Marry and other movement groups’ engagement with the Administration had already achieved a lot. From his first meeting with White House officials early in the first term on, Wolfson had pressed for the Administration to embrace “heightened scrutiny” and a presumption of unconstitutionality for sexual orientation discrimination such as DOMA. In February 2011 the administration made a courageous, principled move, concluding that “heightened scrutiny” does apply to sexual orientation discrimination, that DOMA violated the 14th Amendment of the Constitution, and that, as a result, the U.S. government should no longer defend DOMA in federal court (though the Administration would continue to enforce the law until it had been struck down by a court).

Having the weight of the US government on our side in the movement cases challenging DOMA was a big step forward, and Wolfson and others argued that having gone so far, there was little to lose in embracing the freedom to marry outright. And so in the winter of 2012, Freedom to Marry launched a new effort to create space for, and pressure on, President Obama to “evolve.” The campaign, “Democrats: Say I Do,” called for the Democratic Party to adopt a freedom to marry plank in the party platform at the National Convention later in 2012.

If we look historically at the Democratic platform, it has really been a vision document for where we’d like to go in the Democratic Party. Certainly I think this is a place where most of us believe we need to encourage the Democratic Party to go.

Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH) about Democrats: Say I Do

Freedom to Marry enlisted a cascade of signers: 22 Senators. House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi. Dozens of high-profile mayors. Four former chairs of the Democratic National Committee and honorary chairs of the Obama campaign itself. And more than 35,000 Americans signed a Freedom to Marry petition online encouraging the move.

The Democrats: Say I Do campaign gave marriage supporters real vehicles to mobilize around. And media heavyweights like George Stephanopoulos pushed top Democrats and the White House for their reaction to the calls for a marriage plank in the platform.

Valerie Jarrett, Senior Advisor to President Obama, met often with leaders of the marriage movement, including Freedom to Marry's Evan Wolfson, listening to the concerns and advice on how the President should 'evolve' on the freedom to marry.

In the meantime, Freedom to Marry continued to have high-level conversations with the White House about the most helpful way for the president to talk about his journey when he was ready to. Wolfson urged that the president model the conversations so many Americans were having over the dinner table about their changed understandings of who gay people were and why they wanted to marry, emphasizing the same-sex couples in the first family’s life and the values they share.

On Sunday, May 6, Vice President Joe Biden appeared on Meet the Press and spoke about the freedom to marry. Responding to questions about President Obama’s “evolving” marriage views, Biden said, “I am absolutely comfortable with the fact that men marrying men, women marrying women, and heterosexual men and women marrying one another are entitled to the exact same rights, all the civil rights, all the civil liberties.”

Three days later, on May 9, 2012, President Obama announced that he did, indeed, support the freedom to marry. In an interview with Robin Roberts of ABC News, Obama announced his unequivocal support for marriage between committed same-sex couples. He spoke movingly about his evolution, noting the same-sex couples in his and First Lady Michelle Obama ’s life. He spoke of the religious values important to him, chief among them the Golden Rule. And he spoke of his daughters who had school-friends being raised by gay parents and didn’t think it fair that their families should be treated unequally. President Obama’s moral leadership, and the way in which he explained his change of mind, gave permission to millions of Americans to think anew about their own views and move forward on their journeys to support the freedom to marry.

At a certain point. I’ve just concluded that for me personally, it is important for me to go ahead and affirm that I think same-sex couples should be able to get married.

President Barack Obama, May 9, 2012

In September 2014, the Democratic National Committee’s platform-drafting committee unanimously approved the freedom to marry plank, and speakers throughout the convention – including First Lady Michelle Obama – spoke movingly about their support for the freedom to marry as part of America’s civil rights promise.

President Obama’s touching, authentic interview – and many statements that followed – transformed him into the marriage movement’s “Messenger-in-Chief,” giving permission to more and more voters to move forward. Just weeks after his announcement, in fact, the NAACP officially endorsed the freedom to marry. And it gave an important boost of momentum as the marriage movement sought to take away our opponent’s final talking point, that we could never win a popular vote at the ballot.

President Obama’s support provided the extra push in the 2012 Election that the marriage movement needed, probably accounting for the margin of victory in the Maryland ballot campaign. President Barack Obama won reelection, becoming the first candidate in the country’s history to be elected president while publicly embracing the freedom to marry. And in a triumphant clean-sweep, marriage supporters won at the ballot for the very first time – in 4 out of 4 ballot victories, in Minnesota, Maine, Washington, and Maryland. The tide had turned.

Chapter 9: Winning at the Ballot Box

Turning the Tide and Winning 4 out of 4 Ballot Fights (2011-2012)

For years, the Freedom to Marry team and movement colleagues were hard at work building support, encouraging same-sex couples to share their stories, and mobilizing groups around the country to conduct public education on marriage. With a fragile majority secured by 2010, but still eager to increase that majority so as to avoid the kinds of losses incurred in ballot battles in California in 2008 and Maine in 2009, Freedom to Marry turned to cracking the messaging code for increasing support for the freedom to marry nationwide. The team set a 2012 goal of persuading the reachable-but-not-reached segment of the public needed to solidify the majority and, for the very first time, win a vote of the people. To do that, it was clear that the movement needed to figure out how best to reach the next set of voters in order to get them on board.

For the Mainers United for Marriage Campaign in 2012, the marriage movement launched one of the most aggressive field campaigns to proactively win marriage at the ballot. Read more about the pioneering persuasion work from Maine.

The voters sought out were conflicted, genuinely wrestling with the question, supporting protections for same-sex couples but not yet marriage itself. The marriage movement had not yet provided these people what they needed to change their minds. Beyond that, as was all too evident from the Proposition 8 battle in California, the fragile majority was vulnerable to the opposition’s attacks that same-sex couples marrying would harm children.

Beginning in 2010, Freedom to Marry took on the challenge of cracking the code on messaging. Freedom to Marry’s Director of Public Engagement Thalia Zepatos, working with pollster Lisa Grove, dove into and analyzed existing research data – more than 85 sets – from state marriage campaigns. Zepatos also oversaw the coordination of a confidential research collaborative, the Marriage Research Consortium, with state and national partners working on marriage messaging like the Movement Advancement Project, Basic Rights Oregon, the Center for American Progress, and Third Way coming together to compare notes, avoid duplication and learn from one another.

The responses to one polling question in particular provided a big “aha” moment. On an Oregon poll voters were asked, “Why do couples like me get married?” 74% of people responded “for love and commitment.” When these same voters were then asked, “Why do same-sex couples get married?” the answers were starkly different: 42% responded “for rights and benefits,” and just 37% said “love and commitment.” 22% had no answer for why same-sex couples wanted to get married.

The takeaway was clear: In talking so much about the Constitution and legal consequences of being denied the freedom to marry – true and important though these parts of the case were – the movement was failing to connect sufficiently with a significant slice of people. These people agreed in theory that gay people should not be treated unfairly – but they didn’t understand the importance of marriage to same-sex couples.

The result of the research was a messaging track that emphasized the love and commitment that same-sex couples share – and the idea that these couples want to marry for the same reasons as different-sex couples. Gay people didn’t want to redefine marriage, as opponents asserted; they wanted to join it. Once voters understood better why same-sex couples wanted to marry, their values of the Golden Rule – treating others the way that you would like to be treated—led them to support. The work ultimately brought about videos like this powerful ad from the 2012 Maine campaign:

Having the right message emphasis was not enough, however. Freedom to Marry was also intent on amping up the movement’s message delivery. Armed with the new findings, Freedom to Marry initiated a national public education campaign called Why Marriage Matters to deploy new talking points, videos, and other tools for reshaping the national conversation and enlist partners who committed to using the new messaging approaches. Ultimately, 40 local and national partners signed onto the effort.

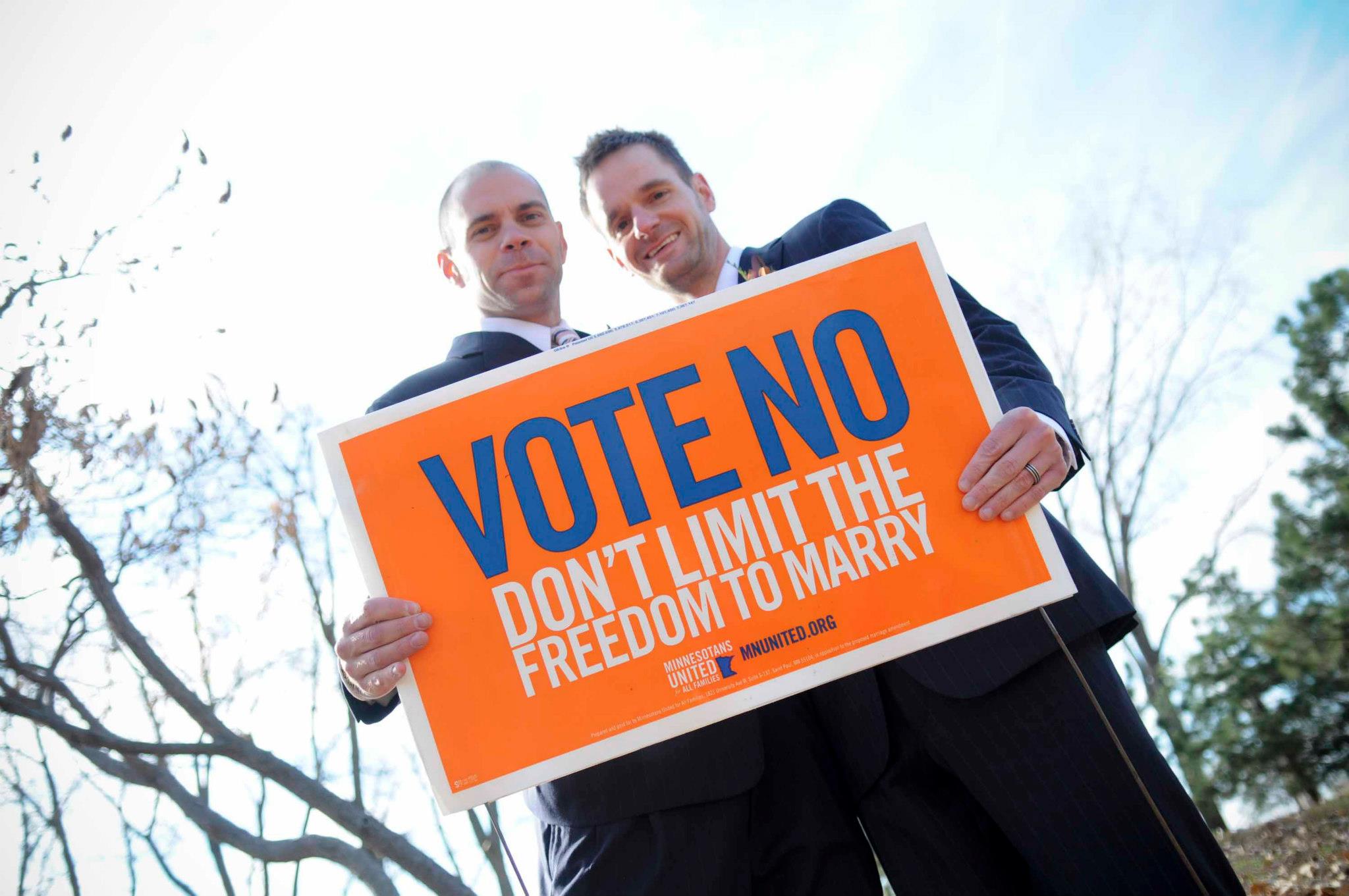

Andy Willenbring and his husband Nick Pautze from Minnesota were just a few of the many same-sex couples who shared their stories with Freedom to Marry to help move marriage forward. Read about all of them here.

The first big public test of this revamped messaging framework was in November 2012, when marriage was on the ballot in Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, and Washington. It was critical that marriage supporters win in at least one battle in order to undermine the opposition’s final talking point – that, when allowed to vote up or down on the freedom to marry, Americans rejected marriage for same-sex couples. Although the rights of a minority should never be decided by the whim of the majority, it was important for the movement to show that the majority support reached in the polling could be manifested in a state-wide ballot campaign .

Washington United for Marriage canvassers helped get the word out about the campaign to win marriage for same-sex couples in Washington.

Of course, winning required more than strong messaging points; the movement also needed to organize more effectively than ever. Freedom to Marry encouraged key local leaders and groups, as well as national organizations and funders, to build campaigns similar to the New Yorkers United for Marriage model. The benchmarks for success laid out and embraced in the state efforts included hiring a talented campaign manager backed with an integrated campaign board, developing significant fundraising muscle, and engaging teams of communications specialists and field organizers – and getting going early. The campaigns were able to pull from Freedom to Marry’s centralized messaging and opposition research, political and legal toolkits, and digital and communications expertise – and Freedom to Marry hosted regular calls to enable them to share communications and field-organizing best practices.

Raising sufficient funds to support robust television ads and field campaigns was key to the marriage campaigns’ successes: By raising early money, the campaigns were able to get TV ads into living rooms, set the terms of the debate, and ensure lower rates for air time throughout the campaign. Operating as an active part of boards and omnipresent consultant as well as a funding engine, Freedom to Marry invested more than $5 million directly into these four campaigns, becoming the largest out-of-state funder in three of the four, and the largest marriage funder in the country.

On November 6, 2012, marriage supporters at last turned the corner on years of ballot losses, sweeping the table in four distinct regions of the United States and vindicating the movement’s hard work to learn how to build campaigns and persuade a majority to reject our opponents’ argument and vote for the freedom to marry.

"When it came to the ballot box, just as gay-marriage opponents were convinced they couldn't lose, some proponents had become convinced they were jinxed. Evan Wolfson refused to believe that. Against all evidence to the contrary, he thought his side could win."

Molly Ball for The Atlantic, in an extraordinary in-depth look at the 2012 marriage ballot campaigns

Minnesotans United Campaign Manager Richard Carlbom celebrates on Election Night 2012. Watch the full video!

The 2012 election could not have provided a more stark contrast with the presidential election only eight years before. In 2004, marriage supporters lost 11 ballot initiatives brought by our opponents in some of the most difficult states in the country, and were unfairly scapegoated by some for the election of a president who supported a federal amendment banning marriage for same-sex couples.

In 2012, the country celebrated unanimous marriage victories at the ballot, and President Obama’s support for the freedom to marry was understood to be a plus, not a minus, for his reelection. We had shifted the political center of gravity, and the momentum for marriage was irrefutable.

Chapter 10: Striking Down Federal Marriage Discrimination

Taking Out the Core of DOMA at the Supreme Court (2013)

The movement turned its eyes to the United States Supreme Court, which just one month later, in December 2012, agreed to hear cases challenging federal marriage discrimination and California’s Proposition 8.

Edie Windsor's love story to her late wife Thea Spyer was at the heart of the legal case that went before the U.S. Supreme Court to strike down DOMA in 2013.

From 2009 on, movement attorneys had brought lawsuits against the federal government to challenge the so-called Defense of Marriage Act. A half-dozen DOMA challenges had been filed in these years, starting with a case painstakingly crafted by GLAD’s Mary Bonauto, who had been waiting since the first Massachusetts weddings for the right time to bring a federal lawsuit. This litigation strategy shaped by GLAD and eventually embraced by others fit within the “Roadmap to Victory” national strategy propounded by Freedom to Marry, which called for synergistic advances on 3 tracks (growing majority support, winning marriage in a critical mass of states, and tackling federal marriage discrimination through legislation and carefully timed litigation).

In nearly all of the cases, trial courts from 2009 on began affirming the unconstitutionality of DOMA, which created a “gay exception” to the normal respect given marriages celebrated in the states, and thus deprived married gay couples of more than 1,138 federal protections and responsibilities triggered by marriage. The cases worked their way through the system, with three federal appellate courts - the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Circuit Courts of Appeals - affirming decisions that struck down DOMA.

One of the later cases was Windsor v. United States, brought by attorney Roberta Kaplan (a partner at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison) and the ACLU on behalf of octogenarian Edie Windsor from New York City. Edie's story was gut-wrenching: After 44 years together, her life’s love Thea Spyer died in 2009 following a 30-year battle with multiple sclerosis. Edie and Thea had married in Canada in 2007, but because of DOMA, their marriage was not respected under federal law, including taxation, and Edie was required to pay a huge inheritance tax bill.

Most likely because of procedural problems with the other cases, the US Supreme Court selected the Windsor case for review, and the nation got a chance to get to know Edie and her compelling story and persona, embodying so much of the movement’s struggle and evolution. The Supreme Court also agreed to hear AFER’s challenge to California’s Proposition 8, Hollingsworth v. Perry.

Although the nation's highest court couldn't - and shouldn't - be directly "lobbied," Freedom to Marry and partners left nothing to chance, seeking to make clear through paid and earned media, digital organizing, social media, and continuing to rack up more wins in the states (as well as overseas, with resonant freedom to marry victories in France and Britain), that the public widely supported the freedom to marry and was ready for a ruling in our favor, and that same-sex couples experienced serious harms as a result of the denial.

Working with state and national partners, Freedom to Marry pushed hard to win more states while the Court considered the cases, securing marriage through legislative victories in Delaware, Rhode Island, and Minnesota., Freedom to Marry also worked together with the ACLU, AFER, GLAD, and HRC to mount an enhanced joint media project amplifying the wins and the growth in national support to create the climate for the Court called for in the national strategy.

Just days before the oral argument in March 2015, Senator Rob Portman (R-OH) made a national splash by publicly declaring that his son had come out to him as gay, and that the Republican now supported the freedom to marry. His was among the first of fifteen pro-marriage announcements from senators around this time, and for the first time, a majority of the United States Senate – 54 senators in total – publicly embraced the freedom to marry for same-sex couples.

Oral arguments in the two cases were held on March 26 and 27, 2013. First up was Hollingsworth v. Perry, where George W. Bush’s former Solicitor General Ted Olson presented arguments in favor of striking down marriage bans nationwide. On the second day of argument, Roberta Kaplan argued in the Windsor case, following the U.S. Solicitor General and others.

The Justices’ remarks during the Windsor argument were encouraging. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg skillfully summed up DOMA’s impact, “It’s not as though, well, there’s this little Federal sphere and it’s only a tax question. It’s, as Justice Kennedy said, 1,100 statues, and it affects every area of life. There’s two kinds of marriages … There’s full marriage, and then there’s sort of skim milk marriage.”

Thousands of supporters of the freedom to marry gathered outside of the nation's highest court on March 27 and 28, 2013 to cheer on the plaintiffs and take a public stand for marriage for all.

Outside of the Supreme Court on both days, thousands of supporters congregated, waving flags and holding up signs in support of the plaintiffs in the cases. When Edie Windsor emerged from the courtroom, the crowd chanted her name, and as she took the stage, she got to the real heart of this fight: “I wanted to tell you what marriage meant to me. Marriage is different. It’s a huge difference. It’s a magic word – for anyone who doesn’t understand why we want it and why we need it, it is magic.”

Three months later, on June 26, 2013, the magic became real for thousands of same-sex couples when the Supreme Court struck down the core of the so-called Defense of Marriage Act. The Perry case fell short of the national victory hoped for, but still delivered an advance for the movement as the Supreme Court let stand a lower court decision restoring the freedom to marry in California, four and a half years after the cruel blow of Prop 8.

DOMA forces same-sex couples to live as married for the purpose of state law but unmarried for the purpose of federal law, thus diminishing the stability and predictability of basic personal relations the State has found it proper to acknowledge and protect ... This places same-sex couples in an unstable position of being in a second-tier marriage.

U.S. Supreme Court Ruling, Windsor v. United States, striking down core of DOMA

Working closely in partnership with the movement legal groups and others, Freedom to Marry had laid the groundwork with the White House and the Justice Department to apply the DOMA ruling to the broadest possible number of same-sex couples—respecting all marriages legally entered into, regardless of where the couple now resided. The Administration’s embrace of that position and swift implementation meant that even married same-sex couples living in states still discriminating would be respected by the federal government and able to share in crucial legal protections under federal law (except for a handful that the Administration concluded it could not make available without further litigation or legislation, most notably some veteran’s programs and Social Security). Binational couples now were able to access the immigration protections long denied their families; people, like Edie Windsor, were no longer subjected to adverse tax treatment; and the bulk of the significant federal safety-net of legal and economic protections and responsibilities finally was made available without discrimination.

In addition to making a powerful tangible difference in the lives of so many, the movement’s strategy and momentum, culminating in the blow to federal marriage discrimination, had now transformed the federal government from being the No. 1 discriminator against gay people to putting its weight on the side of same-sex couples and their freedom to marry.

Chapter 11: Accelerating Momentum

Showing America is Ready for the Freedom to Marry (2014)

The resounding Supreme Court decision striking down DOMA and the Obama Administration’s implementation of federal respect throughout the law and the land flashed the brightest spotlight yet on the untenability of America's house divided - and the inequality and injustice of marriage discrimination where it still persisted in several states.

Throughout 2014 and 2015, as plaintiffs and legal groups filed vital cases challenging marriage bans in every state, Freedom to Marry and national partners beat an unceasing drumbeat calling for the Supreme Court to take a case and rule in favor of marriage nationwide.

Legally, the country was now filled with multiple different "classes" of married couples: Different-sex couples who could marry in any state and move to any state, and whose marriages were respected by the federal government without a question; married same-sex couples whose marriages were respected by both their state and the federal government but not by, perhaps, a neighboring state with a marriage ban; married same-sex couples living in a non-marriage state whose marriages were only respected by the federal government and the growing number of freedom-to-marry states; and couples who weren't yet married because in order to do so, they had to leave their home state and either couldn’t—or didn’t want to—do so. DOMA’s effective demise rawly exposed that same-sex couples were still irrationally being forced to play "now you're married, now you're not," their marriages sputtering in and out arbitrarily, like cellphone reception, depending on their geographic location. The house divided put the government, families, and businesses in an unsustainable position, and without the freedom to marry nationwide, all same-sex couples were still facing real discrimination, especially those living in the states still discriminating.

Spurred by the accelerating public support and political progress, as well as the additional constitutional clarity provided by the Supreme Court’s ruling in Windsor, same-sex couples – many represented by private attorneys and many by the movement's pillar legal organizations (the ACLU, GLAD, Lambda Legal, and NCLR) – filed waves of new federal legal cases seeking the freedom to marry. Within just a few months, every existing marriage ban was being challenged in litigation.

As these cases worked through the courts, momentum for marriage continued to surge: The campaigns Freedom to Marry and local and national partners had built and litigation by the movement legal groups yielded victories in the Illinois legislature and through high court decisions in New Jersey (with a decision not to appeal by NJ Governor Chris Christie) and New Mexico (a unanimous ruling followed by a strong defensive legislative campaign to protect the win). And in December 2013, two decades after the favorable 1993 Hawaii Supreme Court decision that ignited a global movement, the Hawaii legislature embraced the freedom to marry. It was a win two decades in the making.

Then on December 20 came another accelerant: A federal judge struck down the anti-marriage constitutional amendment in ruby-red Utah. The ruling took effect immediately, and the appellate court refused to stay it; on that beautiful Friday afternoon, dozens of couples married in Salt Lake City. The judge’s ruling noted that the growth in public understanding and the climate created by changing hearts in minds had now made clear how the Constitution’s guarantees applied to gay people and their claim to the freedom to marry. Despite multiple requests from the state to halt the implementation of the ruling, the federal 10th Circuit Court of Appeals refused, and same-sex couples continued to marry statewide for over two weeks, until the U.S. Supreme Court placed a hold as the state appealed.

It is not the Constitution that has changed, but the knowledge of what it means to be gay or lesbian.

U.S. District Court Judge Robert Shelby in Kitchen v. Herbert, which struck down Utah's marriage ban in December 2013

The Utah ruling was the first in a nearly unanimous winning streak from state and federal judges across the country, as couples won the freedom to marry Oklahoma, Kentucky, Texas, Virginia, Ohio, Tennessee, and more. A two week-long trial in Michigan led to a March ruling striking down that state’s marriage ban. In May, the first same-sex couples ever in the American South tied the knot when a state judge ruled in favor of the freedom to marry in Arkansas, with no stay. And in Pennsylvania and Oregon, the freedom to marry became the law of the land once and for all when the states' Attorneys General and Governors refused to defend marriage discrimination and chose not to appeal the rulings. The cascade of decisions continued for months - with just a handful of losses accompanying more than 70 pro-marriage rulings between June 2013 and 2015.

Throughout 2014, same-sex couples from across the country married after state and federal court rulings struck down marriage bans. From Arkansas to Utah, Virginia to Idaho, thousands of couples won the freedom to marry in 2014.

Most of these rulings were taken to the appellate courts, and as movement legal groups and private counsel fueled these cases' legal journeys, Freedom to Marry and partners continued making the case in the court of public opinion. In many of these states, the marriage conversation had only recently arrived, and Freedom to Marry wanted to ensure that the energy and momentum across these states propounded two key themes: All of America is ready for the freedom to marry (message to the justices: you can do this), and each day of marriage discrimination is a day where real families suffer real harm (message to the justices: you must do this).

Freedom to Marry launched robust public education campaigns, in coordination with legal partners and state groups, in many states that would be immediately affected by federal appellate decisions – including Why Marriage Matters Arizona, Utah Unites for Marriage, Wyoming Unites for Marriage, and Freedom Oklahoma, among many others. Through its Southerners for the Freedom to Marry, the campaign coordinated with state groups in Southern states on marriage work. Press hits, social media content, and television ads featuring unlikely messengers (Mormon families; a conservative, rural ranch owner with a lesbian daughter: Republican former Senator Alan Simpson of Wyoming) drove the intended narrative and made the momentum palpable and irrefutable across the country and around the Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, the now frequently expedited legal process moved along, with three consecutive decisions from federal appellate courts holding that denying marriage to same-sex couples is unconstitutional. And by the beginning of the fall 2014 term, five different marriage cases sat before the U.S. Supreme Court seeking review. Surely, marriage advocates thought, the Court understood that it was time to directly take on the question of the freedom to marry once and for all.

But on October 6, 2014, the nation’s highest court denied review to the cases, delaying yet again the national victory but allowing the pro-marriage rulings to stand as the law of the land in these circuits, shifting the landscape once again.

It was a shock, but one with a wonderful, instantaneous outcome. The five states in which federal judges had struck down marriage bans (Indiana, Oklahoma, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin) saw those decisions implemented immediately, setting a binding precedent across those circuits. In the weeks that followed, federal judges, bound by the appellate rulings, struck down marriage discrimination in Colorado, Kansas, North Carolina, South Carolina, West Virginia, and Wyoming. And the very next day, October 7, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit unanimously ruled against marriage discrimination, bringing five other states – Alaska, Arizona, Idaho, Montana, and Nevada – over to the right side of history. In that one week alone, the freedom to marry arrived in an additional 16 states.

On October 6, 2015 the U.S. Supreme Court accelerated momentum immeasurably by denying review of many pro-marriage rulings and allowing the freedom to marry to essentially take effect in 16 different states, from coast to coast.